Modern web applications are nothing like what they used to be. The practically limitless bandwidth and indefinite storage space that cloud computing offers.

The microservices that run circles around monolith architecture, breaking down layered apps into small independent components. The single-page apps that load most resources (including the primary DOM elements) once per app cycle so that you can use the site and only update the required dynamic content.

Speed. Flexibility. Easy software integration. Cross-compatibility. Cost-effectiveness. Long story short, modern-day web apps are powerhouses through and through. At the same time, they’re also easily susceptible to remote and local file inclusion attacks. But what is a local file inclusion (LFI) attack anyway?

What is LFI?

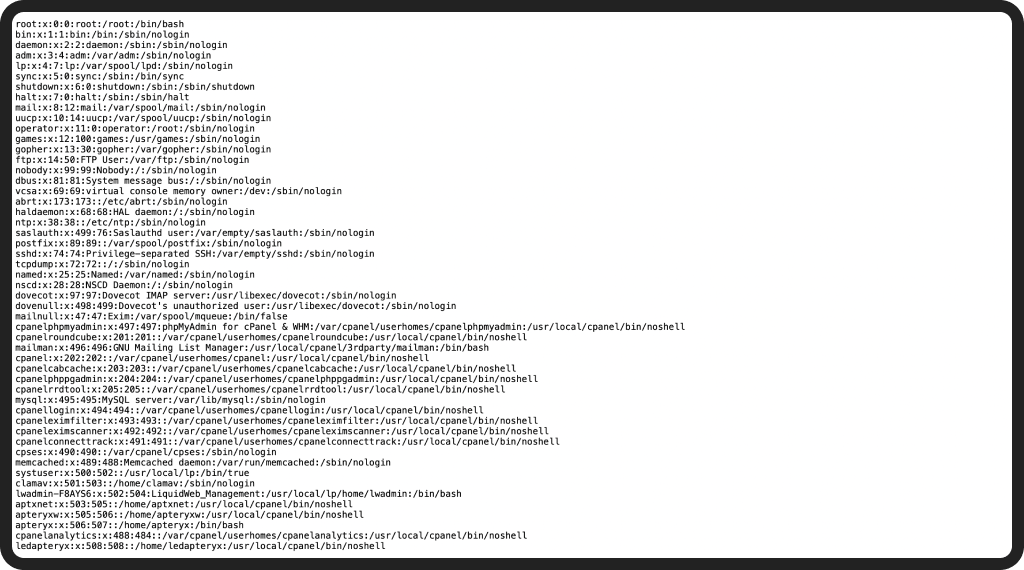

To give you the gist, LFIs are web vulnerabilities that are made possible ‘thanks’ to blunders on the coders’ part. Introducing a security oversight in web apps, careless programmers let unauthorized users access files, seize download functionality, browse the available information, and more.

How is this possible on the hackers’ end? Through the ‘dynamic file inclusion’ loophole. Exploiting these inclusion mechanisms that the developers implement in the app, cybercriminals can throw a foreign file into the original mix. From there, all that’s left to do is run a simple malicious script. Once the script has done its job, you might as well lay out the welcome mat ‘cause it’s going to be free real estate up in the app, and the host will be anyone but you.

But what makes current web apps so susceptible to an LFI vulnerability? Good question.

The issue lies with every server-side scripting language on the web that’s worth its salt. More specifically, with the part where they rely on file inclusions to keep the web apps’ code all nice and tidy (as well as maintainable). Apart from that, file inclusions also let web apps read files straight from the file system, enable download functionality, parse config files, the list goes on.

Where’s the problem, you may ask? The problem can and, more often than not, will arise on the programmers’ side. When the file inclusion mechanisms are not implemented right, experienced hackers will have no trouble exploiting these mechanisms’ inclusion capabilities. Crafting and executing an effective local file inclusion attack, cybercriminals can disclose confidential information, inject a cross-site script (XSS), or unleash remote code execution (RCE).

Sounds a little broad? Let’s see what they look like one case at a time then.

Local File Inclusion Examples

Because exploiting an LFI vulnerability is as technically simple as adding a foreign file to the target’s system, there are multiple ways hackers can do it. These are the most popular methods:

The PHP File Case

According to the Web Tech surveys, as many as 79.2% of sites use PHP. Yes, 79.2% of ALL sites, you read that right. And PHP has its benefits, no doubt about that. At the same time, the very same scripting language also puts most web apps today at risk.

As you know, website and web app developers that use PHP employ these two functions to include one PHP file’s content into another:

- The include() function

- The require() function.

What separates these functions is how they respond to file loading problems. The first, include function signals a warning but lets the script continue nonetheless. The second, require function, on the other hand, creates a fatal error, thus stopping the script.

So, what would a PHP file inclusion attack look like? Something along these lines:

https://example.com/?page=filename.phpThis is a piece of code that would be vulnerable to an LFI attack. See, when the input is not sanitized properly, attackers will have no trouble modifying the input (the example below) and manipulating the app into accessing restricted files, directories, and general information via the “../” directive. Usually referred to as a Directory Path Traversal, this is what it looks like:

https://example.com/?page=../../../../etc/test.txtIn this case, all the cybercriminal had to do was replace the “filename.php” with “../../../../etc/test.txt” in the path URL and, et voilà, they were able to access the test file. At this stage, the intruder(s) could upload a malicious script to your server and access that script using local file inclusion.

To break it down, there are four steps to this process:

- The intruders identify a web lab with inadequate and/or browser input validation from the application’s users.

- The URL string is modified using the “../” directive to make Directory Path Traversal possible.

- The malicious .php file is uploaded to the host server through a backdoor to locate the script using the path traversal method.

- The hacker’s allowed to run his malicious script amok on the host app due to improper validation.

How can you prevent an attack like that?

To start with, you can put up a whitelist with accepted language parameters. When a strong input method is not an option, you can employ input filtering and passed-in path validation. Banking on these methods, you can remove unintended characters and character patterns from the equation.

That said, that will require you to anticipate all problematic combinations of characters. Because that’s the case, a more practical solution would be using predefined Switch/Case statements. With these, the system will automatically determine which files can be included without relying upon URL and form parameters to generate a path dynamically.

The Printed Page Case

At times, you’ll be required to share the file’s output across multiple web pages (as you do with, say, header files). This approach makes the most sense when you want the changes to reflect on every page where the file is included. These files can be plain HTML files that don’t need any parsers on the server’s side to interpret them. They can also be used to highlight separate data entries, including simple text files.

Say you have several .txt files with help texts and would like to make these files available through your web app. With that in mind, you can make them visible through a link, not unlike this one:

https://example.com/?helpfile=login.txtIn this case, the text file’s content is printed to the page straight without storing the information in a database first.

So, how can this lead to a local file inclusion vulnerability?

When you don’t have proper filtering, attackers can easily change the link above to something along these lines:

https://example.com/?helpfile=../secret/.htpasswdIn consequence, they can access the password hashes inside the .htpasswd file, and all the user credentials that this file usually contains. Using these credentials, the digital thieves could then access the server’s restricted areas and wreak serious havoc up there. To add more, the same hackers might even be able to read hidden config files that contain sensitive information (like passwords).

Alright, what’s the counterplay here?

As far as printed page files are concerned, the most effective counterplays are the same that you would execute against download files. Wondering what those are? Great. But let’s figure out what makes this case first.

Download Files Case

There are files that web browsers open automatically when accessed, not unlike PDF files. So, when you want to serve files like these as downloads rather than show them in the browser’s window, you include additional headers, thus instructing the browser to handle it.

With a header like Content-Disposition: attachment; filename=file.pdf in the request, the browser foregoes the ‘opening’ part and downloads the file instead.

To give you an example, some companies have brochures in PDF format so that the site’s visitors can use a link like this to download them:

https://example.com/?download=brochure1.pdfHow can this create an LFI vulnerability?

Easy, that’s how. To be a little more specific, when you don’t sanitize the request, attackers can request to download the files that the very web app is built on, giving them access to the source code. In doing so, they can locate other web apps vulnerabilities, or “just” read sensitive files’ contents.

An extra piece of bad news is that hackers can combine this exploit with the above-mentioned directory traversal method. As a result, the same function might allow them to read the file connection.php source code:

https://example.com/?download=../include/connection.phpAnd, assuming that these hackers find the user database, host, and password values (which is not an unlikely scenario), they will also be able to collect the database using these stolen credentials. At this point, the cybercriminals will have the means to execute database commands and compromise the server structure (unless the database user doesn’t have file write privileges).

What do you do to prevent this from happening?

- Save the file paths in a database and assign individual IDs to each. When you do that, users can see nothing but the ID, so they will be unable to view and change the file’s path.

- Whitelist verified and secured files. From there, you can ignore every other filename and path.

- Don’t put files on web servers that can and, more often than not, will be compromised. Instead, use databases.

- Don’t execute files in specified directories. Instead, make sure the server automatically downloads headers.

Real-Life LFI Examples

We’ve seen many a brave platform fall victim to a local file inclusion attack. And, you’d be surprised, it’s not just some small-time sites that have suffered an LFI blow before. To wit:

Bottom Line

Local file inclusion vulnerabilities are no joke. Some of the biggest platforms in the world have fallen victim to them over the years, and the list keeps expanding. At the same time, as long as you follow the suggestions above and remain vigilant, you should be able to continue working unscathed.

Better safe than sorry: The ultimate LFI prevention cheat sheet